JavaScript 101

JavaScript is awesome for beginning programmers. It’s a great language because it’s easy to learn, and once mastered it’s an excellent tool for building almost any type of website or application. Although JavaScript comes with several frameworks to help developers build applications, these frameworks often complicate things and make the code hard to read.

Javascript was created in 1993 by Brenden Eich.

At that time the web 1. browser was a cutting edge technology the connected the people through the world wide web via internet.

At the beginning, the websites were completely static, built with pure 2. HTML.

Javascript was built as an easy to use 3. High level language.

Today it’s arguably the most popular language in the world.

The standard implementation of JavaScript is called 4. EchmaScript and it’s the default language in every browser.

In fact it’s the only language that runs on a browser except 5. Web Assembly.

But it’s not the only 6. Runtime of JavaScript. It can also run on server via NodeJS, Deno etc.

As the name suggests, it’s a 7. Scripting Language.

That means you can execute code by opening the console in 8. Dev tools on your browser.

Unlike other languages such as C, it’s 9. Interpreted and not compiled.

Although, interpreted is not the accurate term here.

In the browser there is a 10. JS Engine called V8 that makes JS run extremely fast but taking your code and converting it to machine code by a process called 11. Just in Time Compilation.

To use JavaScript in a web page, you’ll first need a HTML document. Inside which there will be a 12. Script Tag.

You can code directly inside the script tag or refer any external JS file using the 13. 'src' Attribute.

You can print hellow world using 14. console.log which is the built in method for printing to stdout.

<html>

<srcipt>

console.log("hello world!")

</script>

</html>

<html>

<script src="app.js"></script>

</html>

There are several different ways to define a variable in JavaScript. The most popular way today is 15. let. It’s a 16. dynamically-typed language, so it’s not neccessary to mention the type of a variable. The variables are commonly named in 17. camelCase. Assigning a value isn’t neccessary but possible.

There are seven 18. Premitive data types.

If we don’t assign a value to a variable it automatically assigned to 19. undefined type which is a premitive type in JS.

However we can explicitly represent an empty value using 20. null and later on we can re-assign the same variable to a 21. string or any other data type.

Any type that’s not premitive will inherit from the 22. Object class. We’ll talk about it later.

let myNumber; // undefined

myNumber = null; // null

myNumber = "eleven"; // string

myNumber = 11; // number

myNumber = new Object();

Here is the list of 7 premitive data types.

- string

- number

- bigint

- boolean

- undefined

- symbol

- null

In JavaScript, the 23. Semicolon; is optional. The JavaScript compiler adds it automatically. In real life JS developers often fight over whether to keep the semicolon or not while coding their project.

However, let isn’t the only way to define a variable.

You can define a variable using 24. const for those which variables can’t be reassigned later.

But the original way to declare a variable was using 25. var.

The only reason to have so many different ways to declare a variable is due to 26. Lexical environment which actually defines where variables work and where they don’t.

There is a 27. Global scope. If we define a variable inside a 28. function, it work in a 29. Local scope inside the function. If we have a statement like if condition, variables can be scoped inside that and it’s called a 30. Blocked scope unless you define it using var. In the case of var it’ll work in the function environment and this is a concept called 31. Hoisting.

let myVar = "global"

function myFun(){

let a = "local"

if (true){

let b = "blocked"

var c = "hoisted 😵💫"

}

}

When function keyword is used by itself it’s called a 32. Function definition. Functions are one of the building blocks in JS. They work by taking 33. Input params or arguments and optionally 34. return a value.

function myFun(a,b){

return a+b

}

myFun(2,3) // returns 5

However, functions are also objects and can be used as 35. Function expressions.

It allows us to use it as variables or to construuct 36. Higher order functions where a function can be used as an arguement or a return value.

const fun = function(a,b){

return a+b

} // Function expression

function higherOrder(f){

f()

return function(){

console.log("done")

}

}

Functions can also be nested inside other functions to create a 37. Closure in order to encapsulate data and logic from the rest of the program.

When you create a premitive inside a function that is stored in the 38. Call stack which is the browsers short term memory.

However while creating a closure, the inner function can act as a variable even after the outer function completes its run.

That happens because in the case of a closure JS automatically stores the data in the 39. Heap which will persist between function calls.

function outer(a,b){

function inner(x){ // closure

return x+1

}

return inner(a) + inner(b)

}

Another interesting thing in JS is 40. this.

If it’s accessed from the global scope it references to the 41 global window in which it’s running.

However if it’s accessed inside a function it’ll refer to the object the function is assigned to.

We can bind a function to a object using the 42. bind function.

console.log(this) // global/window

const person = {

fun: function(){

return this // person object

}

}

function wtfIsThis(){

console.log(this)

}

wtfIsThis.bind(person)

This can be confusing and mordern JS comes with a new syntax of defining functions called 43. Arrow functions.

Arrow functions have their own this value which is 44. Annonymous.

const arrowFun = ()=>{

console.log("Arrow function")

}

One thing to keep in mind, while passing an arguement, premitives are 45. Passed by value which means a copy is created of the original variable.

But, if an object is passed as an arguement, then it’s stored in the Heap and 46. Passed by reference.

A simple way to define an object is using the 47. Object literal syntax or using the 48. Object constructor.

const obj1 = {} // object literal

const obj2 = new Object() // object constructor

An object is contained with key value pairs which are called 49. Properties.

const obj = {

key1: "value1",

key2: "value2",

key3() {

return "value3"

}

}

Objects can inherit properties from each other using 50. Prototype chain.

Every object has a private property that links to exactly one prototype. This differs javascript from a class based 51. inheritance approach.

However, to add into confusion, JavaScript supports 52. OOP with a 53. class keyword.

A class can define a 54. constructor which is called when the object is first created.

You can add properties and optionally add 55. Getters/Setters to access them.

We can add 56. Instance methods too which will be specific to the object or make them global to the class using 57. static method.

class Person{

constructor(name){

this.name = name

this.totalSteps = 0

}

get gender(){

return this.gender

}

set gender(val){

this.gender = val

}

walk(steps){

this.totalSteps += steps

}

static isHuman(){

return true

}

}

In addition to objects, JS also come up with some in built data structures like an 58. Array holding a dynamic collection of indexed items or a 59. Set which holds a collection of unique items.

JS also have a 60. Map data structure which is a key value pair like an object but more easily looped over along with some other featres.

const arr = ["zero", "one", "two"]

const unique = new Set([1,2,3])

const map = new Map([

["foo",1],

["bar",2]

])

Javascript is a 61. Garbage collected language means it automatically removes object from memory when they are no longer referenced in your code. When you have a map all the properties are referenced. However there are 62. WeakMap and WeakSet which have properties garbage collected to reduce memory usage.

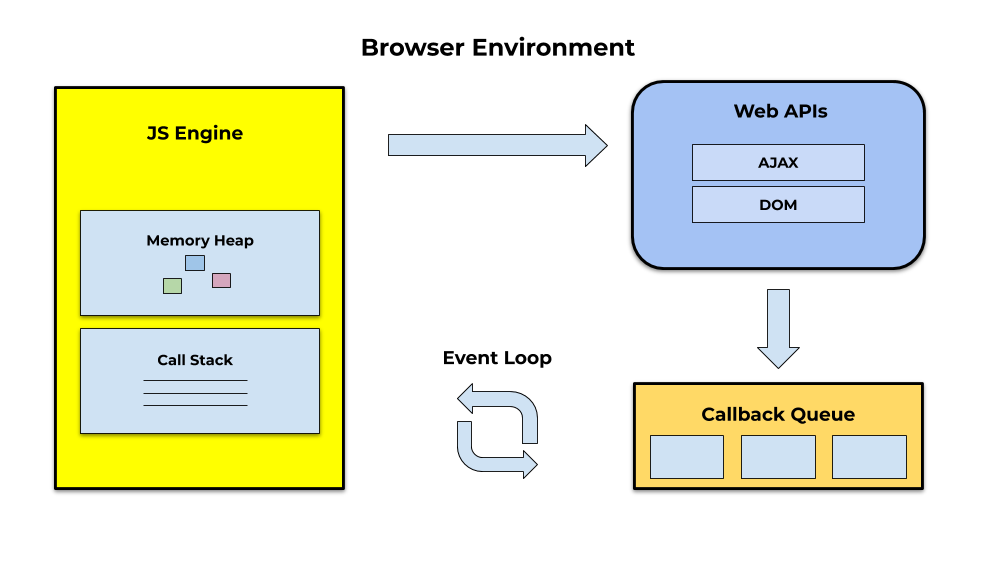

JavaScript has an interesting feture called 63. Non-blocking event loop.

Normally when you write code in a script it executes 64. synchronously which means the next line can’t be executed before the previous line is completed execution.

However it’s possible to write 65. Asynchronous code using event loops in JavaScript which runs in a seperate 66. Thread pool while the rest of the application continues to execute without interruption.

This is really important because mordern websites often have multiple things going on at the same time but they have access to only one thread for computing (67. Single threaded) called the main thread. Without asynchronous code it’ll be impossible to multitask.

An easy way to demonstrate this is 68. setTimeOut function which takes a 69. Callback as an arguement.

setTimeOut(()=>{

console.log("After 2 sec")

},2000)

When Callbacks become too nested, we call it a 70. Callback Hell.

But we have better ways to write Async codes like 71. Promise whose value is unknown right now but it’ll 72. Resolve to a value in the future like calling a 3rd party API and getting the value.

If something goes wrong, the promise can 73. Reject to raise an error.

const promise = new Promise(

(resolve, reject)=>{

// Write code here

if(success){

resolve("success")

} else {

reject("failure")

}

}

)

The consumer of the promise can use methods like 74. then/catch to handle the possible outcomes.

promise.then(success=>console.log).catch(failure=>console.log)

A better way is to use an 75. async function that directly return a promise.

In the body of the function we can process the execution of using the 76. await keyword.

However for exception handling, it’s needed to wrap the await statement inside a 77. try/catch block.

async function fun(){

try{

const success = await promise

} catch(error) {

}

}

As your code grows in complexity, it’s better to use seperate files.

Luckily we can share code between files using 78. ES Modules.

If we want to export something, let’s say a function, we use 79. Default export before importing it to another file.

We can also export multiple things at once from a file using a feature called 80. Named export.

// myFile.js

export default fun(){

console.log("having fun")

}

---

// In other file

import fun from "myFile.js"

fun()

The largest JS package manager is 81. Node Package Manager(npm).

When you install a package from npm, it downloads its code to the 82. node_modules folder.

It also creates a 83. package.json file that lists all the dependency of your project.

Assume you’re building a website. In the web the code will run on a browser which is based on the 84. Document Object Model.

The UI is represented as a tree of html elemets or nodes.

The browser provides APIs to interact with these nodes.

The most important object here is the 85. Document.

The document has a method called 86. querySelector which takes a 87. CSS selector as an arguement and find the html element.

The return object is an instance of the 88. Element class.

To get multiple elements at the same time we can use 89. querySelectorAll method.

window.document.querySelector(".btn")

window.document.querySelectorAll(".btn")

We can listen to 90.Events by adding eventListeners.

const btn = window.document.querySelector(".btn")

btn.addEventListener("click",()=>{

document.body.style.backgroundColor = 'red'

})

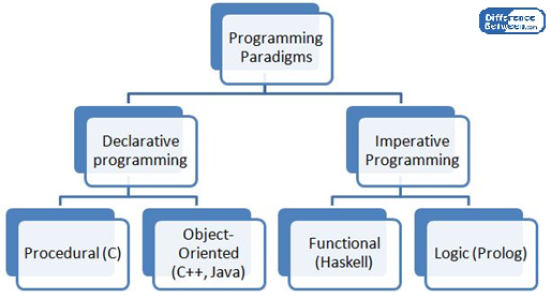

However, this way of coding is not recommended as it results in 91. Imperative code.

Many developers now use frontend frameworks that produce 92. Declarative code where UI is a function of the data.

These libraries encapsulate HTML, CSS and JS into 93. Components.

Most importantly the data inside the components is reactive, that means it can be bound to the HTML from javascript anytime using 94. Data binding.

So, whenever the data changes the UI get updated automatically.

function myComponent(){

const [state, setState] = useState(0)

return (

<div>

<p>{state} times clicked</p>

<button onClick={()=>setState(state+1)}> click me </button>

</div>

)

}

Now, to create a website, you need to compile all you assets and generate a browser usable static code, you need a 95. Module bundler like vite or webpack.

Sometimes JS files gets too big and cause performance issues, which is measured by 96. Network waterfall in the browser devtools.

However, it’s possible to split different javascript files and use 97. Dynamic Imports to run imports lazily.

const lazyBundle = await import("./lazy.js")

JS is not only used in the browser, but also it’s used in the server.

98. NodeJS is the most popular runtime. This opens the door to frameworks like electron which creates the path to full stack and99. Cross platform apps.

Now till this point we got 99 problems and JavaScript is all of them.

T0 get rid of these, please use 100. TypeScript or 101. ESLint which runs static analysis to improve your code quality.

Thank you for reading till the end. Stay healthy and happy coding :)